Anxiety is visible on images of the brain

Knowledge about what happens in the brain during anxiety is increasing. Which signal substances are involved? And why are young people more likely to feel anxious than children and adults? Andreas Frick, a researcher at the Department of Neuroscience, studies anxiety from several different vantage points, using the magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scanner as a tool.

Neuroscience, works at the House of Psychiatry

in Uppsala.

We meet at the House of Psychiatry in Uppsala, where Andreas Frick started a few months ago. He brought with him research funding from the Kjell and Märta Beijer Foundation to study the neurobiological mechanisms behind anxiety and fear.

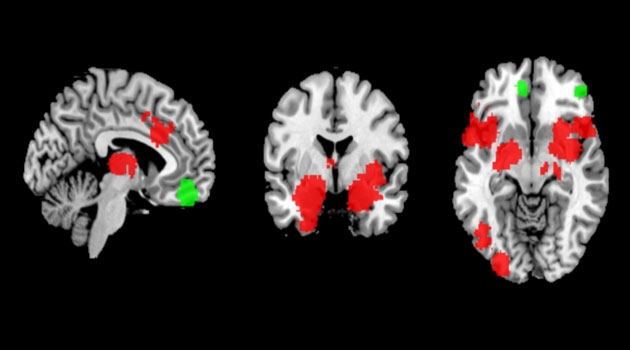

His most important tools are the MRI and positron emission tomography (PET) scanners at Uppsala University Hospital, because through imaging researchers can see which regions of the brain are activated by anxiety. They can also monitor treatment and its results.

“It is somewhat difficult to conduct a brain imaging study, but so far it is the best method. There is something here that cannot be captured in any other way,” says Frick.

The body reacts to threats

What happens in the event of anxiety? Unlike fear, anxiety represents a reaction to a threat that is not present. You feel fear if you meet a bear in the woods, but you experience anxiety if you worry about things that may happen in the future. However, the reaction is the same. The blood flow in the body increases, your mouth becomes dry and various stress reactions cause you to flee, become paralysed or fight for your survival.

“We see changes in the brain with anxiety, including increased activity in the amygdala. This part of the brain acts as a watchdog, sensing what is important in the environment and if a threat exists. Then this activity spreads in the brain, which produces a subjective experience of fear or anxiety.”

Caffeine causes increased anxiety

The researchers want to enhance their view of anxiety by studying the signal substances involved more closely. Andreas Frick has previously studied serotonin and dopamine. Along with doctoral student Lisa Klevebrant, he now will study a signal substance called adenosine. Caffeine in coffee is known to block the receptors for adenosine. As a result, high doses of caffeine produce increased anxiety, especially in individuals with panic disorder.

“In experimental studies where the subjects of the experiment drink the equivalent of four cups of coffee, 50 per cent of them experience a panic attack. So we are going to study whether there is something in the adenosine system that causes individuals who have panic disorder to see things differently. And what happens in the brain when they drink coffee.”

He and his colleague Malin Gingnell, a resident physician at the House of Psychiatry, recently initiated another project. It concerns how anxiety develops over a period of time, from childhood to adulthood, as the brain matures.

“A lot is happening during the teen years, including many changes in neural connections in the brain and the sex hormones that come into play. At the same time, it has been noted that teenagers have more difficulty learning that something is safe after first learning that it is dangerous. In experiments they find it harder than children and adults to learn that ‘this is no longer dangerous.’ We will investigate this.”

Fears can develop into anxiety

During childhood we have various types of fears, such as fear of strangers, separations, darkness and animals. As we become older, our fears become more abstract, such as fear about the future, climate change and war.

Most people overcome their fears as time passes. Others become fixated on their fears and do not get rid of them. Then the fear can develop into an anxiety disorder, which often appears in adolescence.

“We know that the connection between the amygdala and regulatory areas, such as the frontal lobe, develop late, first maturing at the age of 25,” says Frick. “It appears that after a while adults acquire a security memory in the frontal lobe that suppresses the fear memory in the amygdala. As long as the security memory is stronger or the connection is stronger, the sense of security wins out. In teenagers this connection is not fully developed, and we believe this is why anxiety develops.”

Combined treatment helps

He and Malin Gingnell have also conducted research on treatment of anxiety in collaboration with Tomas Furmark, professor of psychology at Uppsala University, and Kristoffer Månsson, a researcher at Karolinska Institutet. Having studied the combination of cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT) and medication, they have concluded that combined treatment works better than CBT alone for most people.

They could also see differences in brain activity that could indicate whether an individual will be helped by the treatment or not.

“We have looked at a part of the brain called the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) and could see that if someone had a high level of activity there before treatment, they responded better to the combined treatment but did not respond well to CBT alone. Those who had a low level of activity there responded well to CBT but not to the combined treatment. We hope this is something that could be developed in the future.”

Not everyone gets help

Today there are large groups of people who never become really free of anxiety, either because they are not helped by treatment or because they relapse.

“We know too little because there are too few long-term follow-ups that have monitored individuals from childhood to adulthood. A treatment may take three months, and the patient is checked before and six months or one year after treatment. But what happens five years afterwards? Ten years afterwards? Will these people who have received a successful treatment continue to feel good? Unfortunately, we do not know that.”

An estimated one-third of the population will suffer some form of anxiety disorder at some point. Not everyone is diagnosed, however, and far from everyone who meets these criteria seeks or gets help, Frick emphasises.

“It costs society an incredible amount of money – in health care costs, lost income and sickness benefits. These are common illnesses that cause people great suffering and that hinder them in life. This provides a great incentive to learn more, to discover new ways of treatment and to improve the treatments we have.”

Annica Hulth