How innovation from Uppsala University can reduce antibiotic-resistant bacteria

Treating severe infections with a combination of antibiotics has long been standard practice in Swedish medicine. Despite this, at present there is no clinical test to prove how well it actually works. Researcher Nikos Fatsis-Kavalopoulos wants to change that.

Some estimates suggest that up to half of all antibiotics given in hospitals are delivered as part of a combination. But no clinical test is used to show the efficiency of this type of treatment.

“The main reason is that existing tests are either not very accurate or very complicated and expensive to perform,” says Nikos Fatsis-Kavalopoulos, researcher at the Department of Medical Biochemistry and Microbiology at Uppsala University and originator of the innovative method CombiANT (combinations antibiotics).

Wants to reduce antibiotic resistance

With their new method, Nikos Fatsis-Kavalopoulos and his team want to offer clinicians an inexpensive, simple and accurate tool to guide them in prescribing antibiotic combinations.

“With an assay like CombiANT we hope to bring personalised testing into the therapy equation and give improved patient outcomes,” he explains.

Nikos Fatsis-Kavalopoulos first encountered the different ways and methods of looking at combination treatment during his doctoral studies. That is when the thought of a more streamlined approach first arose.

“I am originally from Greece, a country consistently among the top in Europe for overprescribed antibiotics and antibiotic resistance. Therefore, contributing to the work of reducing those problems has always been a goal for me,” says Nikos Fatsis-Kavalopoulos.

A slow process

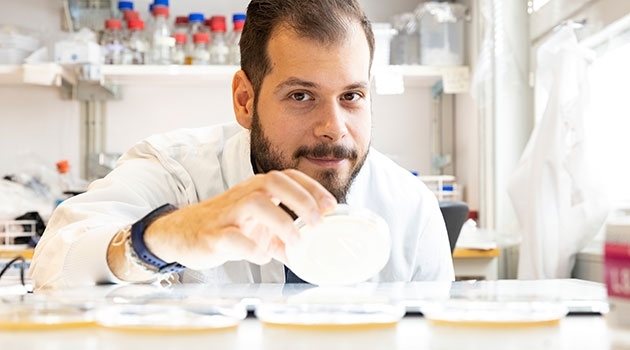

and his team want to offer clinicians an inexpensive,

simple and accurate tool. Photo: Mikael Wallerstedt

Assays of the type that CombiANT offers are, according to Nikos Fatsis-Kavalopoulos, valuable in both research and clinical settings. They first aimed to give researchers a tool that could streamline their work and help produce the kind of datasets the field needs.

“Because the method is thoroughly tested by the academic community, integration in clinical healthcare is a natural next step,” says Nikos Fatsis-Kavalopoulos.

Introducing a new method and making it routine in medical practice is a slow process requiring multiple careful analyses and studies.

“Currently, we are demonstrating our assay’s diagnostic capabilities using archived clinical data. Then we will gradually move toward clinical integration.”

A team effort since the beginning

Right now, Nikos Fatsis-Kavalopoulos and his team are in the process of starting a company and they also applied for a patent on the analytical method and technology. His role in the project and the subsequent company is chief scientist and technology officer. But since the outset the project has been a team effort.

“I can conclusively say that this project would not have happened if any of my teammates were missing; we all brought unique expertise,” he says.

Support from UU Innovation is also something that, according to Nikos Fatsis-Kavalopoulos, has been paramount for the project.

“They have guided us step-by-step, how you go from an idea to a finished, patented product.”

Agnes Loman