Alumnus of the Year discusses path to Nobel Prize

Svante Pääbo vistied Uppsala University and the University Main Building in connection with the Nobel Prize Award ceremony in December 2023. Photo: Mikael Wallerstedt

The foundations of an extraordinary research career were laid at Uppsala University, from Egyptology to medicine and molecular genetics. “In one sense, I learned everything here,” comments Nobel Laureate Svante Pääbo, who has been named Uppsala University’s 2023 Alumnus of the Year.

When Pääbo was awarded the Nobel Prize in medicine last fall, life entered a more intense phase involving lots of requests and invitations.

“I now turn down a lot of things that I would have gladly accepted a few years ago,” he notes.

“It is a cultural phenomenon that the Nobel Prize receives so much attention compared to other prizes. It feels a bit strange that I will never be able to give a talk again without the presenter pointing out that I have won a Nobel Prize. In a sense, this award becomes part of the description of a person.”

Started with Russian

It all started at Uppsala University, where he spent his youth from 1975 to 1986. He started studying Russian and Eastern European studies during his military service as an interpreter. This was followed by Egyptology, medicine and a doctoral thesis in cell biology.

Is there anything you learned that has been particularly useful to you?

“In a way, I learned everything here: Egyptology, human biology at medical school, the then-new molecular genetics at the forefront of the Wallenberg lab where I took my PhD. That's what I'm still doing today.”

Svante Pääbo came to Uppsala University and Gustavianum when he was in secondary school. Photo: Mikael Wallerstedt

Pääbo's first encounter with Uppsala University was at Gustavianum, where he came to take courses in Egyptology. At the time, he was still in secondary school and studying Egyptology at Kvällsuniversitetet (now Folkuniversitetet) in Stockholm.

“I took exams for the courses given by Torgny Säve-Söderbergh, who was a professor of Egyptology, but I was not enrolled at the University. He saved the results in his desk drawer, which were then added to the exam register later on when I became a student.”

Enjoyed being with patients

His studies in Egyptology did not turn out quite as he intended, leading to something of a crisis. Ultimately, he decided to study medicine instead.

“I told myself that I can give it a go and then always change if it’s not suitable.”

His original goal was to go into research, but he discovered that he enjoyed meeting patients in the clinical courses more than he thought he would.

“I found that being a doctor is an extremely privileged job. You get to meet all different people from across society. If you’re a good doctor, you also take an interest in how they live and feel, a bit like priests did in the past.”

This led to a second crisis. Should he focus on research or should he finish his education?

“I told myself again that I could always do a PhD and come back later. And that is still the case now. I don't know how long you can take study leave,” he says with a laugh.

Combined Egyptology and medicine

What happened next was the beginning of the research path that led to the Nobel Prize in medicine in 2022: Pääbo combined his interest in Egyptology with his newly acquired knowledge of molecular genetics.

“When I took my PhD, the idea of cloning DNA in bacteria was fairly new. As I knew that there were thousands of mummified humans and animals in Egyptological collections, it was quite obvious to apply it to them.”

It was initially an evening and weekend hobby which he kept secret from his supervisor Per Peterson at the Wallenberg lab.

Material from mummies

With the help of the then professor of Egyptology Rostislav Holthoer, Pääbo experimented with material from mummies, first from the Victoria Museum in Uppsala and then from a museum in Berlin.

“Using microscopy and staining, I was able to show that there was DNA in the cell nuclei of a mummy from Berlin. I also cloned some human DNA from the mummy. Over the following years, however, it became clear that contamination with human DNA is a major problem, so the DNA sequences probably came from some museum curator or from myself. But a major question was whether the mummy was truly ancient, since there are fake mummies.”

Once again, it was extremely useful to be at a university where expertise in many different areas is concentrated. He was able to simply walk over to the Ångström Laboratory, where Professor Göran Possnert dated the mummy using the carbon 14 method and determined that it was 2,300 years old.

“This is an example of how a comprehensive university can easily conduct interdisciplinary research,” adds Pääbo.

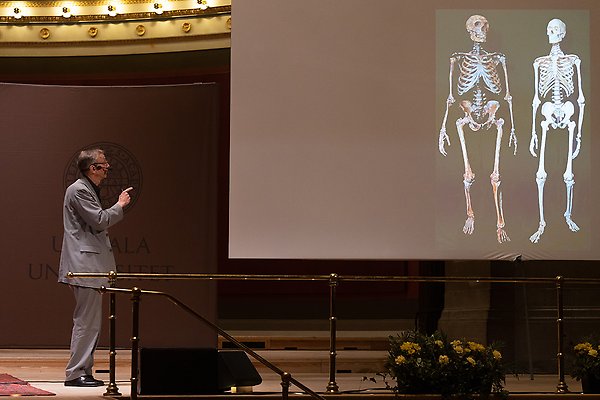

Svante Pääbo giving a lecture at the University Hall, during his visit in Uppsala in December 2022. Photo: Mikael Wallerstedt

Interdisciplinarity key concept

And so it has continued in his eventful academic life, with research in Zurich, California and Munich before co-founding the new Max Planck Institute in Leipzig in 1997. Interdisciplinary collaboration has been at the root of his research into human origins.

“We are completely dependent on palaeontologists and archaeologists who find the objects and often formulate questions. But we also depend on developments in molecular genetics, where we are adapting and developing methods to overcome the technical problems of dealing with old DNA.”

Do you have a favourite place in Uppsala?

“Gustavianum was a very important place to me. I used to go there when I was just a secondary school student taking Egyptology courses, and it was a great experience. But then again, the whole of Uppsala – the University Hospital, Wallenberg Lab and BMC – remains my home environment to some extent," concludes Pääbo.

Annica Hulth

The award Alumnus of the Year

- Each year, Uppsala University awards the title Alumnus of the Year to a former student who has made an outstanding contribution to their professional field, or has accomplished something else worthy of honouring.

- The award is made possible by a donation from Professor John Frederick Morgan-Jones, an Uppsala alumnus from Canada.

- Anyone connected to Uppsala University may nominate a candidate for Alumnus of the Year.

- The decision on who is to receive the award is made by the Vice-Chancellor based on a recommendation from an advisory group.