Image analysis facilitates work of oral and maxillofacial surgeons

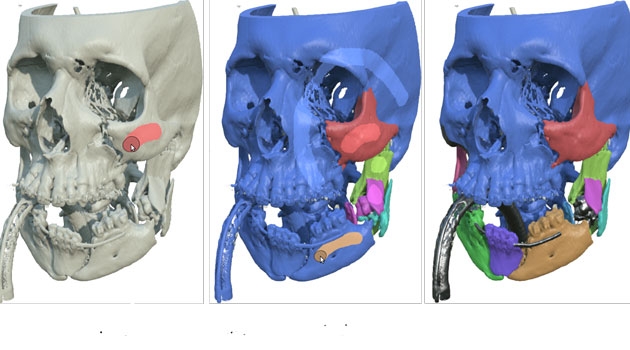

In the future, oral and maxillofacial surgeons will be able to perform an operation on a computer before actually making an incision in the patient. Scanned three-dimensional images of the injured patients are used to make computer models that give the surgeon a better grasp of the true extent of the damage.

Photo: Kajsa Örjavik

“The research will mean shorter operating times, better surgical outcomes and cost savings,” says Ingela Nyström, professor in visualisation at the Department of Information Technology at Uppsala University.

Her research deals with how mathematics and information technology can interact with medicine. She is essentially a mathematician and computer scientist, but while still a doctoral student, she discovered that her applied mathematics could be useful in medicine. Through her research she developed methods for looking at shapes in images on the computer.

“When my supervisor and I asked around if there was interest in this, it turned out that the radiologists at the hospital wanted to be able to view blood vessels on the computer. We then worked on looking mathematically at areas where there was blood vessel constriction.”

Ten years ago, they made contact with oral and maxillofacial surgeons at Uppsala University Hospital, and their collaboration took off. The surgeons needed more precise methods for planning jaw surgery. Now those involved in the project include Dental Specialist Andreas Thor and Plastic Surgeon Andres Rodriguez Lorenzo at the Department of Surgical Sciences.

“If someone has been injured in a fall or kicked by a horse, we can use this method to do a CT scan of the damaged jaw and then put together the broken jaw on a computer like a 3D puzzle before performing the actual operation,” Nyström explains.

“We have built advanced image analysis and visualisation into the system so that you can see how deep the damage is or how shattered a piece of bone is before making an incision in the patient during surgery. You could say that we make the invisible visible!”

The focus right now is on continuing the collaboration with oral and maxillofacial surgeons.

“We have solved the puzzle involving bones – putting them together and making implants. But now we want also to look at soft tissues, because we also need to be able to make skin grafts or move muscles, and that is an area still unexplored. We have slowly begun conducting basic research on this, but we have not yet found the correct funding for the research.”

With this tool, surgeons can look at the skin patch that needs to be removed and find healthy tissue to attach so the wound heals faster.

patientspecific data to draw on the skin.

The latest results of the research make it possible to use patient-specific data to draw on the skin. Surgeons can look at the skin patch they need to remove and then find a corresponding place on skin from the inner thigh. Using the programme and scans of the patient, they can find the healthy tissue at a location where there is also a good blood vessel. By attaching the skin graft with a good blood vessel to the face, healing goes much faster.

“This is the method plastic surgeons have begun looking at,” Nyström notes.

A real challenge in the research is creating models that simulate soft tissue, tendons and muscle tissue. It is more complex to model flexible, soft materials than the rigid skeleton.

The methods developed by Nyström and her colleagues at the Centre for Image Analysis can contribute to shortened operating times and better operating outcomes, which benefits patients. In addition, the methods can help reduce health care costs.

The computerised 3D puzzle method could also be used in other areas, such as by archaeologists who need to piece together ancient urns using fragile pottery shards.

Kajsa Örjavik