Mapping parents’ trust in schools

What school issues have parents been involved in? And what conflicts have arisen between parents and schools? Backman Prytz will investigate these questions in a new research project. Photo: Tobias Sterner/BILDBYRÅN

School strikes were not uncommon in early 20th-century Sweden, with disgruntled parents keeping their children at home. With the emergence of the welfare society, trust in schools as an institution increased. Sara Backman Prytz is delving into the archives to explore the relationship between parents and schools over the past century.

Attendance was somewhat erratic even after compulsory education was introduced in Sweden in 1882, Prytz explains. One reason was that parents had doubts about the school. It was also not uncommon for parents who were unhappy with a teacher to collectively keep their children at home as a protest. School strikes were a widespread phenomenon in the 1920s.

“As the welfare society expands, trust in the school as an institution increases. It also shifts educational issues over to schools. And that idea still exists today – that schools are responsible for the education of children,” adds Backman Prytz, Senior Lecturer in Child and Youth Studies.

Writing a book on trust among parents

Together with Germund Larsson and Joakim Landahl, she has recently launched a research project examining how parents’ relationships with schools have changed from the 1860s to 2012. In particular, it will focus on parents’ trust in the school as an institution. The research project is intended to result in a book and will be based on archival material, such as documents from various parents’ associations and magazine articles.

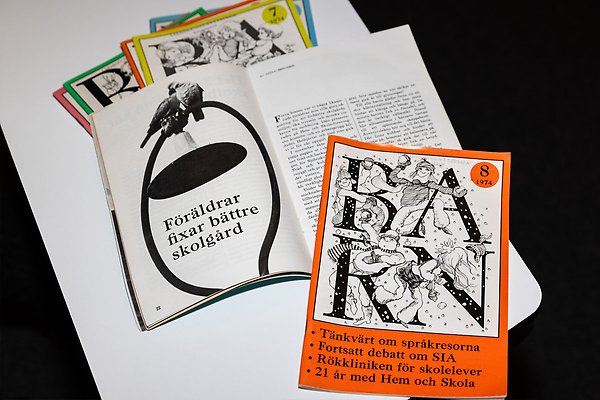

Down in the basement of the Blåsenhus Library there are old magazines from the “Hem och skola” (Home and School) Association which they are currently reviewing. The association is an example of the strong parental collective that developed in parallel with the emergence of the primary school in the second half of the 20th century. Parents organised themselves and worked together on various issues. The Home and School Association, for example, thought that grades should be abolished.

This type of parental collective is not really visible today.

“We see that parents’ associations are not as important anymore. Parents and pupils have become customers in a school market, so there is a greater focus on the individual. And with that comes a willingness to make greater demands on their own school and teachers, rather than collectively focusing on the organisation and shortcomings of the school system. This is something that has evolved over time.”

The Home and School parents’ association published its own magazine. One of its reports dealt with smoking clinics for young people. “This was a hot topic – whether children should be allowed to smoke at school or not”, explains Backman Prytz.Photo: Tobias Sterner/BILDBYRÅN

“School refusers” not a new phenomenon

It is hoped that the research project will provide new knowledge to inform a better debate about schools today.

“It’s important to have a historical understanding as it can also apply to today’s school issues. What is interesting when looking at the archives is that the same questions often arise again and again.”

Backman Prytz gives the example of the relatively new term “school refusers”, which describes children who do not want to go to school.

“Young people having poor mental health and not going to school was also something that occurred in the early 20th century. Later this was called ‘truancy’ and is currently referred to as ‘school refusal’, or problematic school absenteeism. This has always been an important school issue, not least for the parents of these children, but the debate has varied in nature. That makes it difficult to follow whether it really is about the same issue.”

In previous research, Backman Prytz has looked at parental attitudes to sex education in schools. That particular issue is an example whereby parents had objections, as it was considered a matter for the home. Photo: Tobias Sterner/BILDBYRÅN

Facts

The “Tillit och motstånd” (Trust and Resistance) research project: “Ett utbildningshistoriskt perspektiv på svenska föräldrars relation till skolan 1861–2012” (A historical educational perspective on Swedish parents’ relationships to schools 1861–2012), will run from 2024 to 2027. The project has been granted just over SEK 5.9 million from the Swedish Research Council. In addition to project manager Sara Backman Prytz, Germund Larsson from Uppsala University and Joakim Landahl from Stockholm University are also participating.